‘Fragments of Scotch Poetry’: the influences of Robert Burns

In the Autumn of 1786 extracts from three poems under the heading ‘Fragments of Scotch Poetry’ appeared in the Belfast Newsletter. No author was named for these fragments; nor was any of the fragments identified by the title of the poem from which it was taken. Later, the Belfast Evening Post published under the heading ‘Scotch Poetry’ a poem entitled ‘To a youth on his entering the world’. Although it carried a title, again no author was given. The author of the poetry in both newspapers was Robert Burns.

Thanks to former Governor Andrew Gibson (1841-1931) the Linen Hall has one of the largest collections of Robert Burns outside of Scotland. Amassed towards the end of the 19th century, it was acquired for the city of Belfast in 1901 by public subscription and placed in the Linen Hall. With generous funding from the Department for Communities, we are delighted to shine a light on this expansive and historically significant collection, and to explore the wider influences of Robert Burns present in the poetry of our early Belfast and Provincial printed books, and Ulster-Scots collection.

Contributors will bring these collections to life by telling the fascinating stories of those who influenced Robert Burns, his popularity in Belfast and beyond, and enduring influence and relevance – from the Weaver poets to contemporary writers emulating his universal themes of love and nature, and language of everyday life. Spotlighting rare and unique volumes which have been digitally scanned for preservation, and conserved for posterity, ‘Fragments of Scotch Poetry’ is an inspiring insight into the social, historical, and linguistic importance of the poetry in the Linen Hall’s collections.

The Gibson Collection of Robert Burns

Andrew Gibson was born in the village of New Cumnock in Ayrshire on 23rd December 1841. As an adult he moved to Glasgow to take up work as a shipping agent for G&J Burns, pioneers in providing steamer services between Scotland and Ireland, at their Jamaica Street office.

Andrew married Mary Sinclair Brown in August 1869 in Glasgow, and they had five children, two sons and three daughters. The Gibson family moved to Belfast in 1881 when Andrew was appointed as an agent for G&J Burns in the city. By 1910 he was the Belfast agent for both Burns and Cunard lines and served on the Harbour Board from 1915 until 1925.

Andrew Gibson was described by Kyle Hughes in ‘The Scots in Victorian and Edwardian Belfast’ as ‘Belfast agent for the Burns and Cunard shipping lines, harbour commissioner, and prominent member of numerous cultural and sporting organisations’ and one of the most well-known ‘Belfast Scots’ of the period. Outside of his work, Andrew had many interests and contributed in a variety of ways to the social and cultural life of his adopted home. He was a leading cultural figure in the city of Belfast, serving as President of the Belfast Burns Club, Belfast Scottish Association, and vice President of the Belfast Benevolent Society of St Andrew. His interest in sport is illustrated by his being President of the Belfast Bowling Club, and of Cliftonville Football Club – both sports being heavily dependent upon the influence of Scottish migrants.

Andrew Gibson was also a Governor of the Linen Hall. We know from the minute books that he attended the annual meeting of 15th February 1894, and that he was co-opted to the Board at a meeting of the Governors on 22nd February 1894.

Gibson was instrumental in reviving the Ulster Journal of Archaeology and played a key role in organising the second Belfast Harp Festival and was also involved with the Belfast Shakespeare Festival in 1905.

The village of New Cumnock where Andrew Gibson was born, with associations to both William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, is believed to have been familiar to Robert Burns as a frequent visitor, with friends in the area. Andrew Gibson could therefore have been particularly drawn to Burns because of where he was born and grew up. There may also have been a familial pull, as following the death of Andrew’s mother, his father married Janet Lapraik. Janet was the granddaughter of John Lapraik, who was a good friend of Robert Burns.

That Gibson became an important and prolific collector and bibliographer of Robert Burns while living in Belfast was reflecting not only an enthusiasm of his own but also one shared in his adopted town and province.

FAREWELL TO THE LONG-LOVED SHORE:

EMIGRATION IN THE ANDREW GIBSON COLLECTION

by Linde Lunney

Andrew Gibson’s marvellous collection of Burnsiana and books of poetry written by Ulster authors is a two-way or even a three-way mirror. It reflects something of the collector, his background and his interests, and it reflects a view of the world within which Gibson lived.

Gibson was an important and prolific collector and bibliographer of Robert Burns, with meticulous documenting, indexing and notation of his collection. ‘The Oxford History of the Irish Book’ edited by James H Murphy succinctly captures Andrew Gibson’s aspirations as a collector: ‘He particularly wished to acquire every edition of Burns he could accrue and went to great lengths to do so.’ The development of his collection was described as ‘a labour of love, in which he took the keenest interest and justifiable pride’.

Gibson’s handwritten catalogue from 1894 contains 266 titles, which may suggest much of the collection was built after this.

It has been noted that the Gibson Collection of Robert Burns contained some 782 distinct Scottish, English, Irish, American, and Continental editions, and ran to over 1,000 volumes.

And awareness of the collection was certainly heightened when Gibson lent over 300 of his texts to the Burns Exhibition in Glasgow in 1896, held to commemorate the centenary of the death of Robert Burns. As well as lending from his collection, Andrew Gibson was the only person outside Scotland to be elected to the executive committee that organised the exhibition. The Exhibition was held in the 6 huge galleries of the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts on Sauchiehall Street and ran from July to October 1896.

At a meeting in the Linen Hall in December 1900 under the Chairmanship of the Lord Mayor Sir Robert McConnell it was agreed: ‘the collection of Burns and Burnsiana, formed by our fellow-townsman, Mr Andrew Gibson, should be acquired for the city’. In his speech Rev Thomas Hamilton of Queen’s College commented on the importance of the collection: ‘In no public or private library in these kingdoms, or in the world is there a collection like it’.

The purchase price was £1,000, which was raised by public subscription.

The collection was variously described as ‘unequalled’, and ‘without exception the most complete embodiment of the widespread influence of Burns’.

A key draw was that the collection should find a home in the city in which it was formed.

The collection contains significant holdings of Burns’s editions published in the poet’s own lifetime, and rare and limited volumes.

The ceremony of transfer of the collection took place in the reading room of the Library on 17th December 1901, with an exhibition of the rarer items, and it has been the Linen Hall’s privilege to be the custodian of this collection since.

Scotia’s poets

Besides Robert Burns, Andrew Gibson had an avid interest and actively collected works of Thomas Moore. In addition to being an acknowledged authority on Moore, Gibson was a recognised expert on the Scottish poet Allan Ramsay (1684-1758), writing ‘New Light on Allan Ramsay’ which was published in Edinburgh in 1927.

It has been said that James Thomson (1700-1748) was the most celebrated Scottish poet of the 1700s until Robert Burns. In 1725, Thomson travelled from Scotland to London where he published his masterpiece, The Seasons. Thomson broke with the witty, artificial poetry style of the times, turning instead to nature for his subject matter, writing vivid descriptions of natural scenes in rich verse. His style led to the romantic movement of the later 1700s.

In turn, Robert Fergusson (1750-1774) is seen as the bridge between the generation of Allan Ramsay and most later writers in Scots, and is an acknowledged inspiration to Robert Burns, with synergies between their respective poems having been widely documented. And such was the impact of Robert Fergusson on Robert Burns that when Fergusson died and was buried in an unmarked grave on the west side of the Canongate Kirkyard in Edinburgh, Burns privately commissioned and paid for a memorial headstone of his own design in 1787, which was erected in 1789 to the man he described as ‘Scotia’s Poet’. The gravestone reads:

Here lies Robert Fergusson, Poet

No sculptured marble here, nor pompous lay

No storied urn, nor animated bust

This simple stone directs pale Scotia’s way

To pour her sorrows o’er her poet’s dust

Robert Burns in print

The first collection of Robert Burns’s poetry was published in Kilmarnock in 1786, with an Edinburgh edition following. His poetry was probably first printed outside Scotland in Belfast – initially in newspapers – and then in September 1787 James Magee issued his Belfast edition of the poems of Robert Burns to an appreciative audience.

Magee’s edition, as the advertisement freely admitted, was taken directly from the ‘last Edinburgh copy… with a copious glossary not in some of the former editions and embellished with an engraving of the head of the author, which is esteemed a striking likeness’.

Essentially, the 1787 James Magee edition was ‘shamelessly copied from the Edinburgh edition in a smaller format and at a cheaper price’.

Collapsing the distance:

aspects of Burns, texts and readers in Ulster

by John Erskine

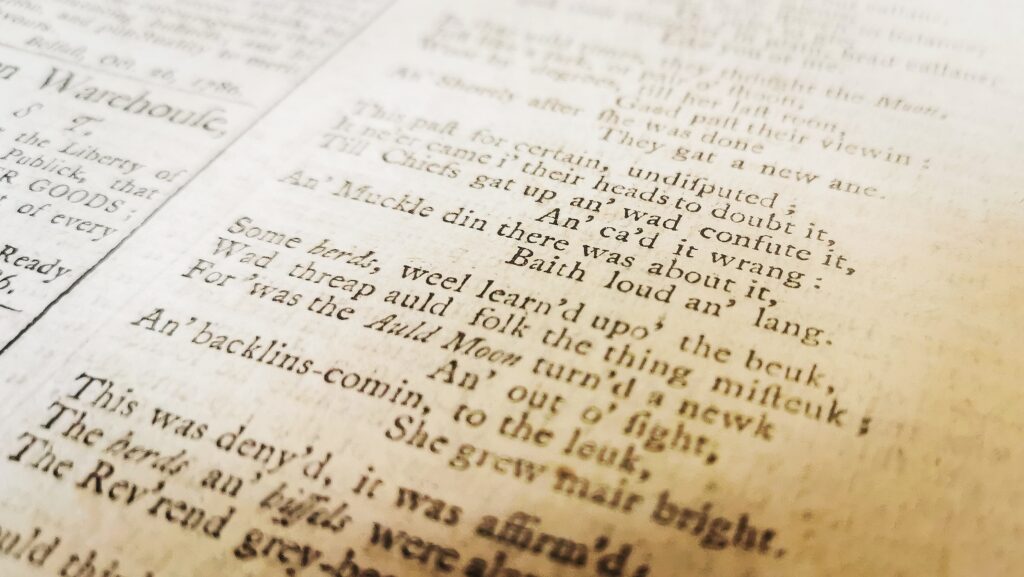

In the autumn of 1786 readers of the Belfast News-Letter (which appeared twice a week in those days) opened their issue for the start of November to discover within it a column entitled ‘Fragments of Scotch Poetry’.

WeAVING WORDS

In the subsequent years, Robert Burns’s popularity increased, and it is often said that Burns and the bible were the only two books found in Ulster homes in the 19th century. The proximity of the west coast of Scotland and the east coast of Ireland is undoubtedly a factor in Robert Burns’s appeal in Ulster. There are synergies of landscape and dialect which resonate.

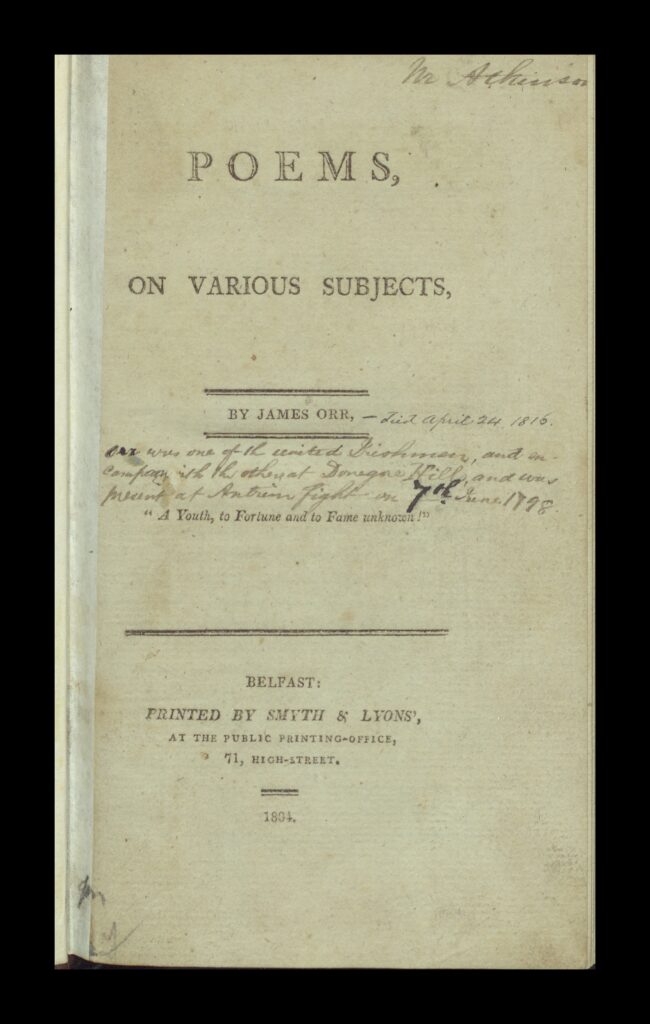

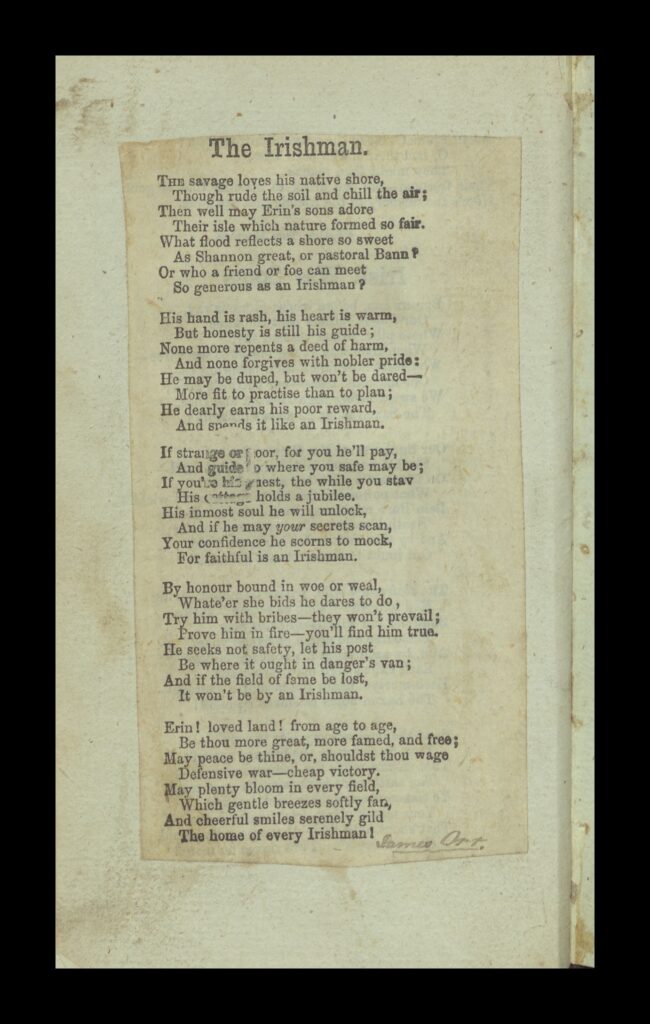

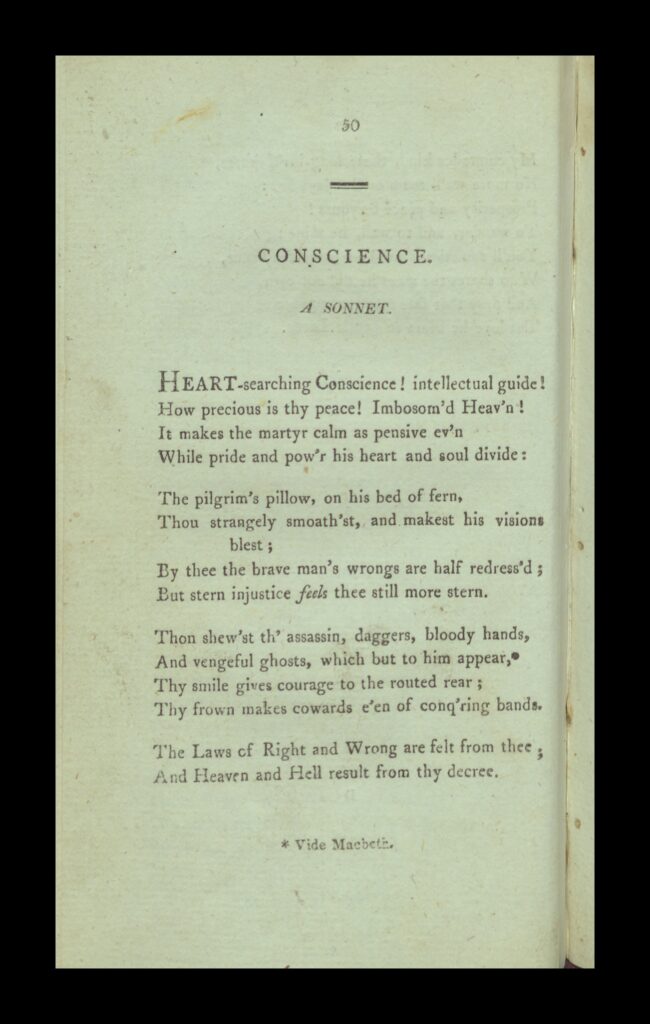

And Robert Burns was of course very influential on Ulster poets who feature in the Linen Hall’s early Belfast and Provincial Printed Books, and Ulster-Scots collection – poets such as James Orr (1770-1816), Samuel Thomson (1776-1816), and David Herbison (1800-1880). Samuel Thompson, the Bard of Carngranny, dedicated a volume of his poetry in 1793 (‘Poems on different subjects, partly in the Scottish Dialect’) to ‘Mr Robert Burns, the Ayrshire poet’, and in 1794 travelled to Dumfries to meet and exchange poems with Burns. While James Orr, the Bard of Ballycarry, is often referred to as ‘Ulster’s Burns’.

A voice for the oppressed: James Orr (1770-1816)

by Dr Carol Baraniuk, University of Glasgow

Born in 1770, a weaver by trade, Orr grew up in the County Antrim village of Ballycarry, a delightful spot, site of the romantic, ruined Templecorran church, which enjoys magnificent views across the Irish Sea to Scotland. Orr’s era used to be routinely defined as an ‘age of revolutions’.

A introduction to Samuel Thomson

by Lolly Spence

Samuel Thomson (1766-1816) was a County Antrim poet who has since become known both as the ‘Father of the Rhyming Weavers’ and as ‘The Bard of Carngranny’. The Rhyming Weavers – or Weaver Poets – is a collective term for a group of poets who mostly wrote during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Hugh Porter (1780-1839), known as the Bard of Moneyslane, is another poet who wrote in Ulster-Scots, and whose one published volume of poetry, ‘Poetical Attempts’, is a treasure of the Linen Hall’s collections. The poems are vivid descriptions of his life as a linen weaver and have been hailed as an evocative reminder of a long past era.

A contemporary, in particular of James Orr, is the Larne born poet and, illustrating the richness and diversity of writing of this time, novelist James McHenry (1785-1845).

Dr James McHenry and his Life and Times

by Dr David Hume

James McHenry, poet, novelist, and doctor is buried in a modest grave in the Smiley family plot at St. Cedma’s Churchyard in Larne. The small gravestone accords him his literary due, as “Author of O’Halloran, &”. But it does little to explain that buried here is Larne’s greatest author, and someone who also made their mark on American literature in the 19th century.

A linen weaver by trade, David Herbison, the Bard of Dunclug’s passion for poetry was such that it is reported he saved all he could from his earnings and walked the twenty-six miles from Ballymena to Belfast to buy the works of Allan Ramsay; returning a year later for the poems of Robert Burns.

One of the highlights of this project was uncovering a letter written by David Herbison found inside a copy of his seminal Children of the Year.

My Native Tongue

I have not the command of the language that I have of my native tongue. In fact, I think that my ideas are more barren in English than in Scotch. Robert Burns

Together the Gibson Collection of Robert Burns, the Linen Hall’s early Belfast and Provincial Printed Books, and Ulster-Scots collection chart poetry written in Scots and Ulster-Scots from the 18th century through to contemporary writing.

One of the earliest examples from our collections being the Ulster Miscellany from 1753.

'Scotch Poems' from the Ulster Miscellany (1753)

by Dr Frank Ferguson, Ulster University

By eighteenth-century standards The Ulster Miscellany is a big book. At nearly 400 pages long it announces that the province of Ulster should be reckoned with as a place of literary interest. This follows in the tradition of several other miscellanies published in the first half of the century that sought to publicise the cultural worth, or lack, of various locales.

This rich literary tradition is fostered and encouraged today by initiatives such as the Linen Hall’s Ulster-Scots writing competition. The competition offers a welcome opportunity both to highlight and promote the Ulster-Scots collection at the Library, but also to enhance the collection with writing from contemporary Ulster-Scots writers and to inspire engagement with Ulster-Scots writing. One of the winning writers from the competition, Gary Morgan reflects on writing in Ulster-Scots, and shares one of his poems.

Ulster-Scots: What it means to me

by Gary Morgan

Many people would associate Ulster-Scots culture with bards, bands and bonies. I certainly would not argue against that, as culture can mean different things to different people, but in my view, it represents so much more. Ulster-Scots culture is reflected in the food we eat, the music that we listen to and the literature we read. It has contributed to rural life and influenced the way many of us speak today.

This online exhibition contains a sample of the hundreds of volumes scanned to create digital surrogate copies and conserved for preservation under funding from the Department for Communities. We are grateful to the Department and all contributors for helping us to showcase these treasures, and ensure the volumes have a future as rich as their past.