CREATION

The border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland (formerly the Irish Free State) was created in the early 1920s, at a time when a lot of national borders were being drawn and redrawn after World War I. The border in Ireland emerged out of a long-standing conflict between nationalists who sought varying levels of independence from Britain, and unionists who wanted Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom.

Home Rule

From the second half of the nineteenth century and into the beginning of the twentieth century, Irish nationalists campaigned for ‘Home Rule’ – a parliament in Ireland which would have control over domestic affairs. Irish unionists were opposed to Home Rule for several cultural, economic, and political reasons. Under Prime Minister William Gladstone, two Home Rule Bills were introduced: one in 1886 which was defeated in the House of Commons, and another in 1893 which was defeated in the House of Lords. When the Third Home Rule Bill passed the House of Commons in 1912, the House of Lords no longer had the power to veto it completely, but rather to delay it for two years.

World War 1

The Home Rule Bill was set to become law in September 1914 when World War I broke out in Europe, and the implementation of Home Rule was shelved until the war ended, with a special provision for Ulster to be determined. The unexpected length of the war, coupled with events such as the Easter Rising during it, meant that the political context in Ireland was very different when the war ended in 1918 than when it began in 1914.

Newspaper reprint of the second Home Rule Bill, 1893.

Below Inside cover of the official programme for the Ulster demonstration against Home Rule, 1912.

By the end of the 1910s, Ulster’s exclusion from the Home Rule Act was almost inevitable, but the precise form this would take was still to be decided. In late 1919, the British Government formed a committee headed by Irish unionist Walter Long to determine Ulster’s fate.

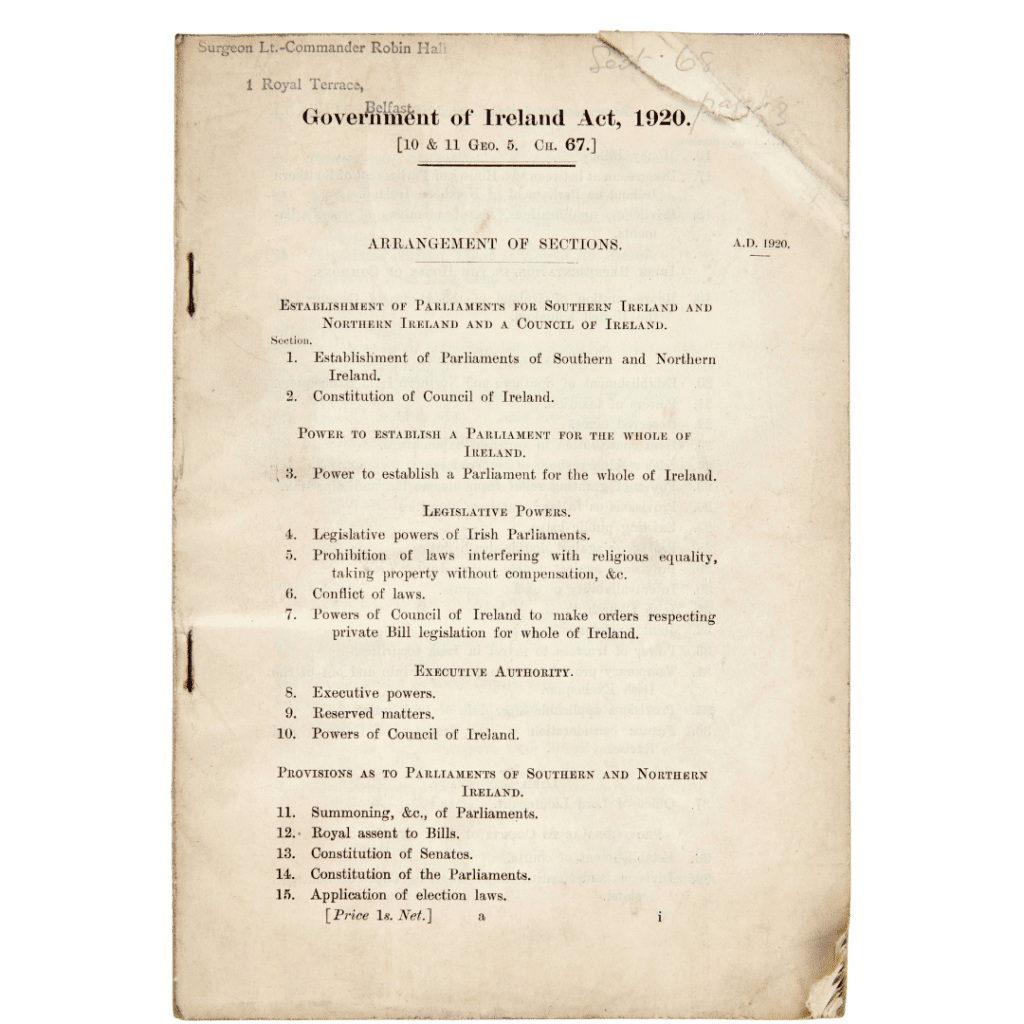

The Government of Ireland Act

The ‘Long Committee’ suggested that all nine counties of Ulster should be excluded, but the British Government yielded to Ulster Unionist demands for six county exclusion in the Government of Ireland Act, which passed in December 1920. The Government of Ireland Act established two separate parliaments for ‘Northern Ireland’ and ‘Southern Ireland’, and came into force on 3 May 1921. Northern Ireland encompassed the six most north-easterly counties and Southern Ireland comprised the remaining 26 counties. While almost all nationalists, both north and south, disagreed with partition and refused to participate in either parliament, most unionists within the six counties accepted the creation of Northern Ireland and worked to make it a functioning political entity.

Front cover of a pamphlet depicting the six counties that make up Northern Ireland in red.

Copy of the Government of Ireland Act.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty

The border was further solidified in late 1921 through the Anglo-Irish Treaty. Signed by a delegation of Irish nationalists and the British Government, the Treaty created the Irish Free State, which granted more independence to Ireland than through the Government of Ireland Act. Article 12 of the Treaty, however, allowed the Government of Northern Ireland to opt out of the Irish Free State, which would then trigger the formation of a Boundary Commission. The Government of Northern Ireland opted out of the Irish Free State as soon as it could, on 7 December 1922.

Custom Posts

From 1 April 1923, the border became more economically and physically defined. Although the Irish Free State Government alleged their opposition to partition, they nonetheless imposed tariffs and taxes on goods which came from Northern Ireland, enforced through the erection of custom posts and checkpoints along the border.

‘A Commission consisting of three Persons, one to be appointed by the Government of the Irish Free State, one to be appointed by the Government of Northern Ireland and one who shall be Chairman to be appointed by the British Government shall determine in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions, the boundaries between Northern Ireland and the rest of Ireland.’ – Article 12 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.

The Boundary Commission

Ulster Unionists opposed the Boundary Commission, fearing that it threatened the viability of Northern Ireland. Consequently, the Government of Northern Ireland refused to nominate a commissioner, leading to the British Government appointing one on their behalf.

The Commission convened in November 1924, and then met with a range of individuals and organisations formally and informally throughout the spring and summer of 1925. The Boundary Commission’s recommendations were leaked in late 1925, provoking outrage in the south, which led to an agreement between all three governments to suppress the Commission’s report. The border was thus left as it was in the Government of Ireland Act, and this is how it remains today.

Anti-Boundary Commission Literature published by Ulster Unionists in 1924–1925.

The Border Poll

The only official referendum ever to be held on the Irish border was in 1973. On 8 March 1973, the electorate in Northern Ireland was asked whether they wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom or leave to join the Republic of Ireland (formerly the Irish Free State). The majority of nationalists boycotted the referendum. On a turnout of 58.7 percent, almost 99 percent voted to remain within the United Kingdom. Discussions about the future of the border have increased since the result of the United Kingdom referendum on whether to leave the European Union in 2016, leading to more calls for a border poll. Under the terms of the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement, the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland is responsible for ordering a border poll if it appears likely that a majority of the electorate would vote to leave the United Kingdom.